Thich Nhat Hanh - Life, Books, Teachings

Thay's Life

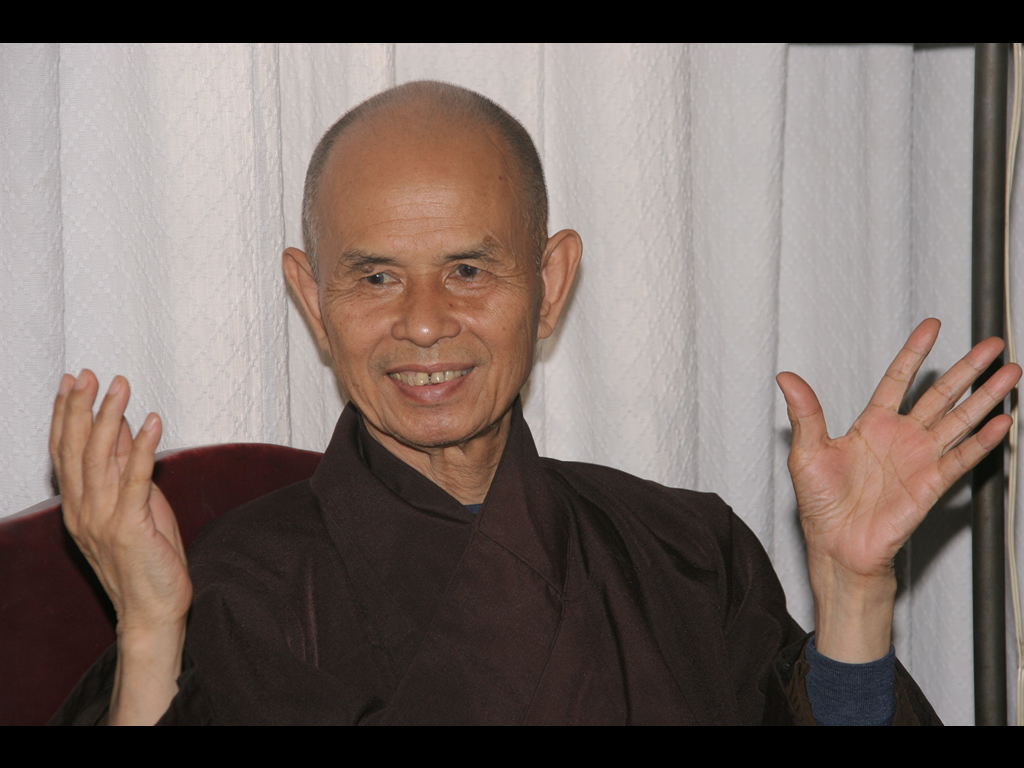

Lovingly referred to as Thay (“teacher” in Vietnamese), Thich Nhat Hanh is a global spiritual leader, poet, and peace activist, revered throughout the world for his powerful teachings and bestselling writings on mindfulness and peace. Thich Nhat Hanh is a gentle, humble monk – the man Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. called “an Apostle of peace and nonviolence” when nominating him for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1967.

Born in central Vietnam in 1926, Nhat Hanh was ordained a Buddhist monk in 1942, at the age of sixteen. Just eight years later, he co-founded what was to become the foremost centre of Buddhist studies in South Vietnam, the An Quang Buddhist Institute. In 1961, Nhat Hanh came to the United States to study and teach comparative religion at Columbia and Princeton Universities. But in 1963, his monk-colleagues in Vietnam invited him to come home to join them in their work to stop the US-Vietnam war. After returning to Vietnam, he helped lead one of the great nonviolent resistance movements of the century, based entirely on Gandhian principles.

When war came to Vietnam, monks and nuns were confronted with the question of whether to adhere to the contemplative life and stay meditating in the monasteries, or to help those around them suffering under the bombings and turmoil of war. Thich Nhat Hanh was one of those who chose to do both, and in doing so founded the Engaged Buddhism movement, coining the term in his book Vietnam: Lotus in a Sea of Fire. His life has since been dedicated to the work of inner transformation for the benefit of individuals and society.

As a scholar, teacher, and engaged activist in the 1960s, Thich Nhat Hanh also founded the Van Hanh Buddhist University in Saigon, La Boi publishing House, and an influential peace activist magazine. In 1966 he established the Order of Interbeing, a new order based on the traditional Buddhist Bodhisattva precepts.

On May 1st, 1966 at Tu Hieu Temple, Thich Nhat Hanh received the ‘lamp transmission’ from Master Chan That. A few months later he traveled once more to the U.S. and Europe to make the case for peace and to call for an end to hostilities in Vietnam. It was during this 1966 trip that he first met Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who nominated him for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1967. As a result of this mission both North and South Vietnam denied him the right to return to Vietnam, and he began a long exile.

Thich Nhat Hanh continued to travel widely, spreading the message of peace and brotherhood, lobbying Western leaders to end the Vietnam War, and leading the Buddhist delegation to the Paris Peace Talks in 1969.

Plum Village and other centres worldwide

Thay continued to teach, lecture and write on the art of mindfulness and ‘living peace,’ and in the early 1970s was a lecturer and researcher in Buddhism at the University of Sorbonne, Paris. In 1975 he established the Sweet Potato community near Paris, and in 1982, moved to a much larger site in the south west of France, soon to be known as Plum Village. Under Thich Nhat Hanh’s spiritual leadership Plum Village has grown from a small rural farmstead to what is now the West’s largest and most active Buddhist monastery, with over 200 resident monastics and over 10,000 visitors every year, who come from around the world to learn the art of mindful living.

Plum Village welcomes people of all ages, backgrounds and faiths at retreats where they can learn practices such as walking meditation, sitting meditation, eating meditation, total relaxation, working meditation and stopping, smiling, and breathing mindfully. These are all ancient Buddhist practices, the essence of which Thich Nhat Hanh has distilled and developed to be easily and powerfully applied to the challenges and difficulties of our times.

Based on the model of Plum Village, there are now centres in the US, Germany, Australia, Thailand, Hong Kong and another centre near Paris. Thich Nhat Hanh has published over 100 titles in English, ranging from classic manuals on meditation, mindfulness and Engaged Buddhism, to poems, children’s stories, and commentaries on ancient Buddhist texts. They capture the Zen Master’s lifetime of teaching, scholarship, creativity and spiritual discovery.

Ahimsa is in the process of setting up a centre in India modelled on Plum Village.

Books and Calligraphy

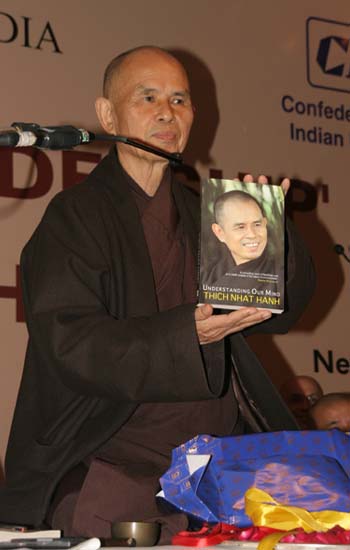

Thich Nhat Hanh has published over 100 titles in English, ranging from classic manuals on meditation, mindfulness and Engaged Buddhism, to poems, children’s stories, and commentaries on ancient Buddhist texts. They capture the Zen Master’s lifetime of teaching, scholarship, creativity and spiritual discovery.

Ahimsa Trust has been instrumental in translating some of the works of Thay, as Ahimsa represents the Thich Nhat Hanh community in India and South Asia. In India publishers like Full Circle, Aleph, Jaico, Harper Collins and Amber have been publishing the works of Thay. His books have also been translated into other languages. ‘Old Path White Clouds’ has been translated into Hindi, ‘Jahan Jahan Charan Pade Gautam Ke’ and published by Hind Pocket Books. This book has also been translated into Sinhalese, Marathi and Nepali. Other books like ‘The Stone Boy’ has been translated into Hindi and published by Full Circle. Other publishers like DC Books and Cre-A are also publishing Thay’s books in other languages in India.

Many years ago, after burning out from love, life, work and political activism, in my search for a spiritual teacher who could guide me on how to ‘be peace’ rather than ‘fight for peace’, I arrived at a retreat for artists at the Ojai Foundation in California. In the five days that Thich Nhat Hanh taught there, I felt for the first time that rather than merely having a concept or notion of peace, I truly experienced peace. Each day we walked in meditative awareness among the sage bushes in the foothills of the Los Padres mountain, ate meals in silence, contemplated existential questions and learnt how to live happily in the present moment.

Thay (as he is known to his students – it is pronounced like the first half of ‘Thailand’) taught by his example, his metaphors and his practical, poetic, philosophical words. He taught us to cultivate the energy of mindfulness which would allow us, even in the most mundane of activities, to touch the miracle of life in the present moment.

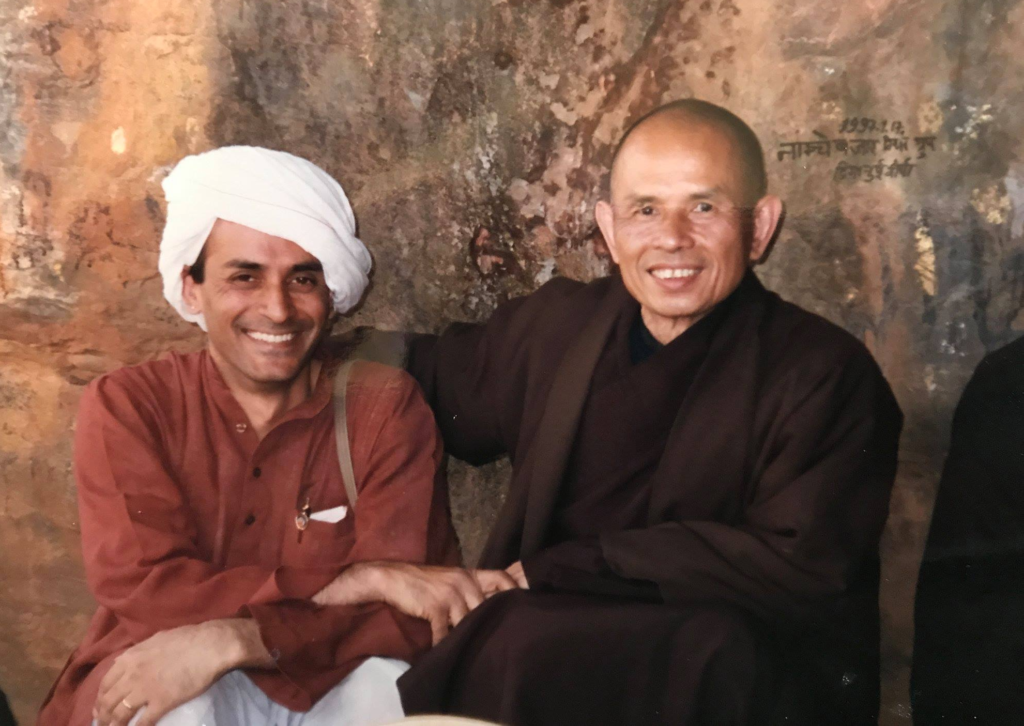

When I returned home, I wrote him a letter to say that if he was interested in visiting India I would be happy to arrange something for him. As it happened, he had been planning to make a pilgrimage in the footsteps of the Buddha, and he requested me to organise this journey. It was in those 35 days of travel

in close proximity that I came to see that I had found my spiritual guide, someone who blended everyday activities with a spiritual significance, someone who epitomised ‘engaged Buddhism’. His insights allowed me to link my inner practice to my outer social, political and ecological concerns. As I discovered, I was not the only one whom he had affected in this way.

Thay had been instrumental in influencing Martin Luther King Jr. to come out against the war in Vietnam (which is Thay’s homeland); in fact, King nominated him for the Nobel Peace prize in 1967, a year when it was not conferred on anyone. His Holiness the Dalai Lama said about Thay that ‘he shows us the connection between a person’s inner peace and peace on earth’. He has been revolutionary in many ways, being one of the first monks in Vietnam to ride a bicycle, to change the language of liturgy from classical Chinese to Vietnamese, to bring much greater gender equity in the Buddhist sangha (community), and even to introduce practices such as hugging meditation in order to make the Dharma more accessible to Americans. Unique in many ways, Thich Nhat Hanh was once described by another Zen master, Richard Baker Roshi, as a cross between a cloud, a snail and a piece of heavy machinery.

On the actual path of the Buddha, Thay allowed me to understand the Buddha as a human being: one who had struggled with the existential questions of his time and discovered a path of awakening. Thay suggested that I continue this practice of pilgrimage that the Buddha had suggested; it would help me to understand the Buddha and his teachings better. Each winter since 1988, I have gone on pilgrimage along the path of the Buddha, and at some time during each year I have gone on retreat with Thich Nhat Hanh.

As I got to know the Buddha better, he struck me as having been a practical man, whose core teachings were ways to overcome suffering and attain happiness, peace and liberation. His concerns were rooted in our human experience, and not in metaphysical speculations on the existence of God or questions about eternity.

Thay and Shantum in a cave near Vulture Peak, Rajgir

His discovery of the non-self and interdependent nature of reality – for which Thich Nhat Hanh coined the word ‘inter-being’ – and his teaching that this understanding can be gained by one’s own effort through the practices of mindfulness, concentration and insight, were revolutionary at the time. They continue to be counter-intuitive in a world where so much emphasis is placed on individuality and the self.

Thich Nhat Hanh has taken the ancient teachings of the Buddha, developed in India 2,600 years ago, and made them relevant to our time. The perennial questions of what binds us to suffering and what can give us a sense of inner freedom and awakening remain; but the means of practice have been skilfully adapted. Thich Nhat Hanh has taken many of the practices out of the monasteries and secularised them for an everyday audience. His school of Zen Buddhism, rooted in the ‘Mind only’ ( Vijñānavāda ) school of Mahayana

Buddhism, speaks about a store of consciousness which holds many seeds, both wholesome and unwholesome.

The basis of Thay’s practice is to water the seeds of mindfulness, thereby becoming aware of our mental formations as they arise. In this way we become aware of the roots of those mental states and, in an internal weeding of our mind’s garden, we cull or transform the unwholesome seeds and cultivate or quicken the wholesome ones.

Thay has made the Buddha Dharma accessible to people from all walks of life, among them teachers, psychotherapists, lawyers, businessmen and women, prisoners, parents and children. This has helped build a worldwide community of practitioners, both lay and monastic. In India, besides having regular gatherings of practitioners, we hold retreats and days of Mindfulness, especially in the field of education and applied ethics.

Thay’s simple yet articulate exposition and explanation of complex concepts makes him an artist with words. His poetry speaks eloquently to our hearts and minds. His deceptively simple teachings help make such simple acts as smiling and conscious breathing into practices of self-calming and of deep seeing.

Shantum Seth – August 2017

Books published by Aleph Book Company, India

Thich Nhat Hanh’s Zen calligraphies have been exhibited in North America, Europe and Asia. These eloquent ink artworks capture his insights, peace, and gentle compassion.

In my calligraphy, there is ink, tea, breathing, mindfulness and concentration. This is meditation. This is not work. Suppose I write ‘breathe’; I am breathing at the same time. To be alive is a miracle and when you breathe in mindfully, you touch the miracle of being alive. Thich Nhat Hanh

Thich Nhat Hanh began to write calligraphies in 1994, for the titles of books, songs and articles appearing in print. Using traditional Chinese ink on rice paper, he developed a new style of Zen calligraphy in the western Roman script. Calligraphies such as This is it, I have arrived, I am home and The bread in your hands is the body of the cosmos began to be framed on the walls in his practice centres around the world.

The calligraphies act as a bell of mindfulness for the viewer, reminding us to arrive in the here and now, and touch the wonders of life.